Shoes of the Audience

Everyone has their reasons.

He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.

By the time a film you have made is seen by an audience, it has probably been on your mind for weeks, months, even years. Everything – every narrative beat, every nuance, every shred of characterisation, every twist and turn – is, presumably, crystal clear to you. To borrow a line from a vintage limerick that Mackendrick occasionally recited to students, you are hopefully able to answer this question at every turn of your film story: Who is Doing What With Which and to Whom? You must be able to justify the inclusion of every image and sound that you have shot and edited into the final project. You should know exactly why certain elements of the story have been emphasised. You must understand and be able to explain the distinct motivations of each and every character at every beat of your story. Your planning around such things has, doubtless, been meticulous.

The problem is that this isn’t always so easy. There is almost a psychological trick to overcome, one that some people seem to struggle with. It can be difficult to step out of your own brain and take a close look at what you have created, what the audience is actually seeing, and what conclusions they are perhaps making. The deep knowledge you have of your story will help you as a filmmaker not one bit if you are unable to consider everything that you are striving to put onscreen from a different – and just as important – point of view. As each image, sound, scene and sequence of the story plays out, it’s vital that you learn to place yourself into the shoes of your future audience and consider precisely what it is, at every moment, they are most likely looking at and thinking about. How will this shot land? Fail to ask this simple question, then come up with an answer, and the result could be that audiences are confronted by a story that makes little sense to them, or (and this doesn’t seem quite as egregious) that feels confusing.

When asked by an interviewer if students make the same mistakes, Mackendrick replied, with his usual shrewdness: “I don’t even like the word ‘mistake,’ because that seems to suggest that there are rules, things you should do or not do, and there aren’t. Any statement about film in general has got to be from a personal point of view, and all you can say is, ‘Yes, that’s fine, if that’s what you want to do.’ There are two mistakes that you can make in film. One is to create in the audience an impression that you didn’t want to make and don’t need. The other one is fail to make the impression you did want. These things are so basic that they mean there are no rules at all.” Ensure – up to a point – that what your audience knows and is feeling is what you planned on them knowing and feeling. When writing a scene, when framing a shot, when editing a sequence, ask yourself: what will this appear to be from the audience’s point of view? How does this specific image play to them?

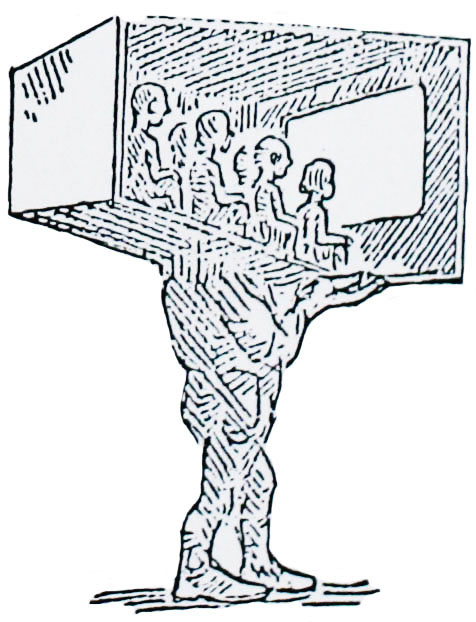

Mackendrick’s broad thoughts on this subject are, as usual, simple and effective. In his student handouts he writes the following, accompanied by an image of what he calls “The Movie House on Your Shoulders.”

On the set, a film director is apt to have a preoccupied, absent manner, as if his mind was inhabiting another time and space. In a way it’s true. He’s not really there. In spirit, he has removed himself into the future and is already sitting in some movie theater beside his audience, looking through a rectangular window into another world, an imaginary world. A member of the audience, he is feeling what they feel, reacting as they react. The abstracted attitude of the director comes from his attempt to screen out all activity that is irrelevant to the creation of this new time and place. He looks at the mobs of people surrounding him on the studio floor in a weird way, blind and deaf to much that is going on. His mind is fragmented. Concentrating on what only he can see, he is busy rearranging the short, narrow segments, those disorientating bits and pieces of a not-yet-assembled reality which will be seen and heard through that open window of the screen in the movie house. While he is on the studio floor, the crew thinks that he is out of his mind, since he appears to see what they cannot see and hear what they cannot hear. He is living not only in the future but, in another sense, also in the past. A while ago, when he was in the scriptwriting stage, he was able to “see” the movie fairly well. Now, looking through the viewfinder, he is working to a memory of that vision, using it as a guide to the hundreds of decisions he has to make as he puts together all the pieces of the jigsaw.

© Mackendrick Family Trust