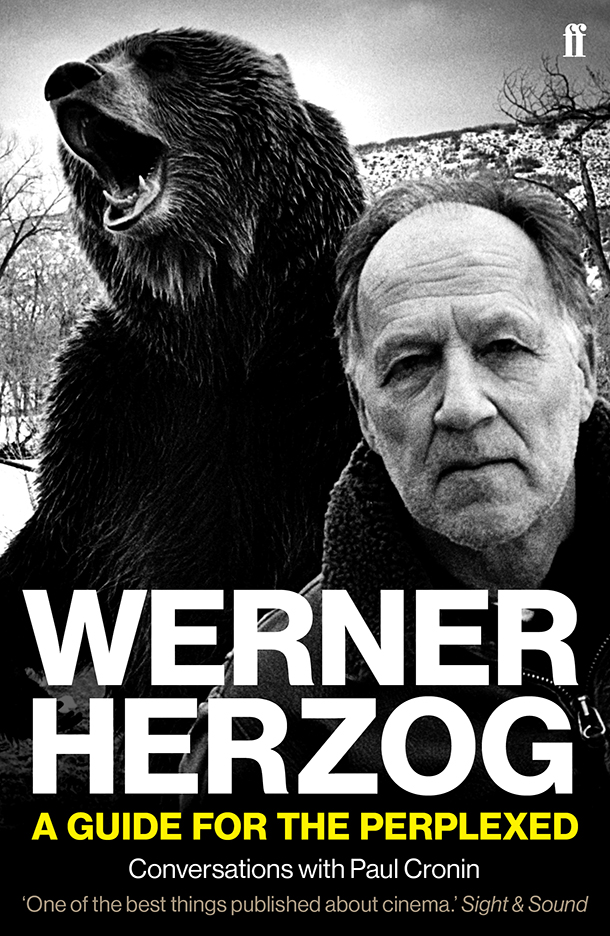

Werner Herzog

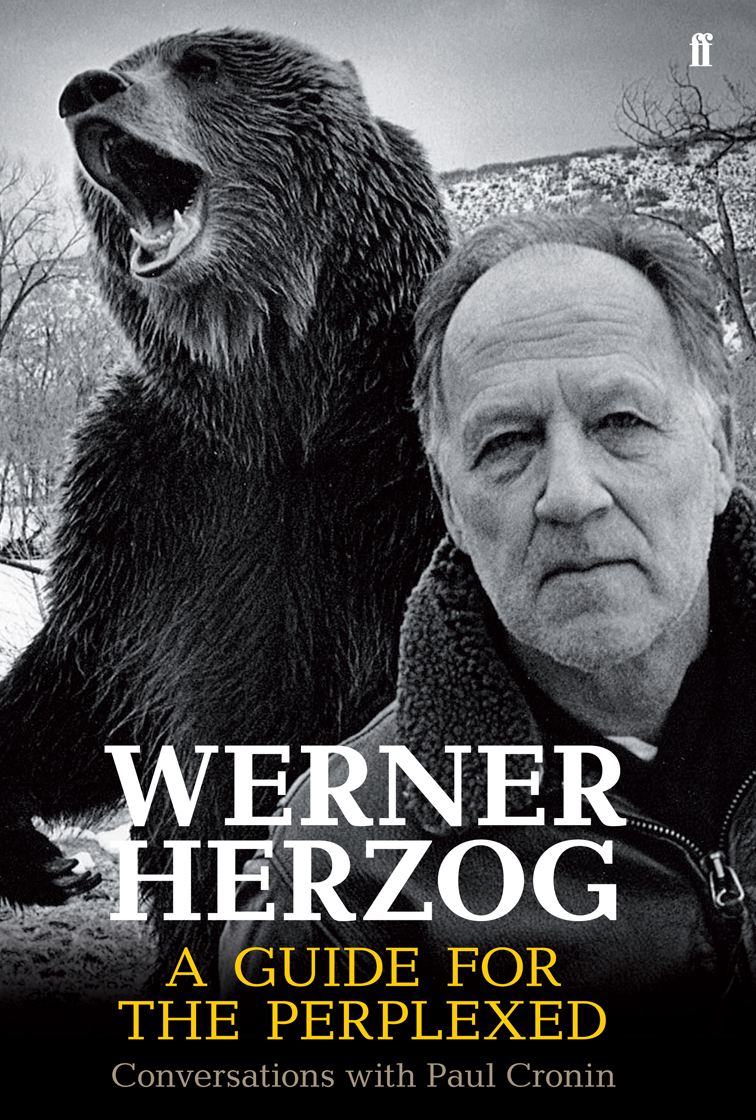

In A Guide for the Perplexed: Conversations with Paul Cronin (2014) Werner Herzog interweaves details of his background and theories of life and the universe around us with discussions of his books, his Rogue Film School, his likes and dislikes, and every one of his dozens of films, from A Lost Western (1957) to From One Second to the Next (2013). By so doing, Herzog lays bare his worldview, presenting us with an instruction manual, with tools for living and tools for dreaming. Lesson #1: Get used to the bear behind you.

Also contains: a foreword by Harmony Korine, a 32-page colour photo insert, translations of Herzog’s poems from 1978 and diaries from 1984, an essay by Herb Golder, an afterword by physicist Lawrence Krauss, a bibliography and filmography. The book’s introduction is here. A piece of the filmmaker trilogy, the book is a re-written and expanded version of Herzog on Herzog (2002).

Life is about oneself against the world.

Paul Bowles

Although his place in film history is assured, Herzog’s work has always been a by-product of his furious “extra-cinematic” inquisitiveness and infatuations. He has forever been nourished by a wondrously eclectic range of interests that might have propelled him equally in the direction of mathematics, philology, archaeology, history, cookery, ant wrangling, football or science. The fact that it’s cinema the multifarious Herzog has involved himself with is, to a certain extent, irrelevant to our tale, one of dedication, passion and determination. This book is the story of one man’s constant and (almost) always triumphant confrontation with a profound sense of duty to unburden himself, and for that reason alone it’s worth our attention.

Werner’s work ethic and drive, impressive decades ago, remain formidable, and his ability to maintain creative integrity and generate new ideas is exhilarating. There is a wonderful moment in Conquest of the Useless, the published version of his journal, written – Walser-like – in microscopic script during production on Fitzcarraldo. While playing in an imaginary football match in Lima, Werner struggles to distinguish between players on his team and his competitors. When the referee refuses to halt play so one side can exchange its jerseys for those of a less confusing colour, Werner concludes that “the only hope of winning the game would be if I did it all by myself… I would have to take on the entire field myself, including my own team.” When it comes to his films, this energy is perpetually generated by, as he calls them, “home invaders,” those ideas that steal inside his head, to be wrestled to the ground in the form of a screenplay, film or book. Herzog’s filmmaking has never given him consolation as such. It’s a blessing and a burden. He never has to worry about whether a good idea for the next film will reveal itself because, like it or not, the throb is there long before the one at hand is complete. When Herzog writes that the image of a steamship moving up the side of a mountain seized hold of him with such power it was like “the demented fury of a hound that has sunk its teeth into the leg of a deer carcass,” we presume there isn’t a project he has involved himself with over the past fifty years that has taken hold with any less urgency. As David Mamet has written, “Those with ‘something to fall back on’ invariably fall back on it. They intended to all along. That is why they provided themselves with it. But those with no alternative see the world differently.”

Nearly fifteen years ago, when I started work on this project, Werner hadn’t attained the godlike status the world now accords him. For the past twenty years he has lived on the West Coast of the United States, most recently a few miles from Hollywood, where he is his own master. While some folks wait bleary-eyed for calls from their agent, Werner rarely picks up for his own (“For decades I didn’t even have an agent and even today don’t really need one”), and has forever preferred the company of farmers, mechanics, carpenters and vintners to filmmakers. In California he is free from European rigidity, even if he still feels a powerful intellectual and emotive connection to his homeland. In 1982, a year before her death, Herzog’s mentor Lotte Eisner wrote that Werner is

German in the best sense of the word. German as Walther von der Vogelweide and

his love poem “Under the Lime Tree.” German as the austere, fine statues of the

Naumburg cathedral, as the Bamberg horseman. German as Heine’s poem of

longing “In a Foreign Land.” As Brecht’s “Ballad of the Drowned Young Girl.”

As Barlach’s audacious wood statues, which the Third Reich sought to destroy.

And as Lehmbruck’s “Kneeling Woman.”

Today, studio executives adventurous enough to try and entice Werner into more conventional enterprises show up at his door, though the issue, as Anthony Lane has written, “is one not of Herzog selling out but of Hollywood wanting to buy in.” Werner’s comrade Tom Luddy, co-founder of the Telluride Film Festival (where the Werner Herzog Theater opened in 2013), describes him as a “pop icon.” Having outlived countless trends, Herzog has moved into the primary currents and is celebrated worldwide, as he suggested would happen. “I think people will get acquainted to my kind of films,” he said in 1982. Werner feels no shame in admitting that the respect of those he respects somehow keeps him going, or, at least, temporarily lessens the burden. But his belief in his abilities has never seriously wavered, which means details of the peaks and troughs of his career – which essentially speak to his treatment at the hands of professional reviewers and the ticket-buying public – are barely touched on throughout the pages of this book. Herzog pays little attention to the chorus. And why should he? It isn’t antagonism he feels towards such folk so much as indifference. His ferocious need to make films and write books will forever trump everything, regardless of the obstacles.

By offering up the background to each of his films and how they were made, Herzog offers details of form, structure and – indirectly – meaning. As he articulates his techniques, ideas and principles in the conversations that follow, his way of looking at the world is made clear. His “credo,” as he puts it, “is the films themselves and my ability to make them.” Truffaut once explained that making a film is like taking a boat out to sea, the director at the helm, forever attempting to avoid shipwreck (in his Hitchcock book he describes the process as a “maze of snares”). Being tossed about on the waves is the very nature of filmmaking, a state of affairs only an amateur would whine about. (“I’m not into the culture of complaint,” Herzog says. To his fictional son in julien donkey-boy: “A winner doesn’t shiver.” Physicist Lawrence Krauss: the universe doesn’t exist to make us happy.) In short: you’re always asking to be sunk. Or, per Herzog, who describes himself as a product of his cumulative humiliations and defeats, filmmaking “causes pain.” In discussing the day-to-day experiences and hard graft of the cinema practitioner, in stressing how vital it is for each of us to follow our own particular channel, in acknowledging that the name of the game is faith, not money, A Guide for the Perplexed furnishes the reader with an oblique ground plan to help navigate the rocks and manage the daily calamities.

Not coincidentally, these are the same ideas that underpin and flicker steadily throughout the three days of Herzog’s extemporizing at his irreverent and sporadically executed three-day Rogue Film School. Nietzsche tells us that “All writing is useless that is not a stimulus to activity.” Similarly, Herzog declaims that his ultimate aim with Rogue is to be useful rather than explicitly didactic, something I suspect he succeeds in, much to the delight of all those youthful, awestruck participants. His rousing description of the filmmaker and how he needs to move through the world, con- fronted at every turn by obstructions, paints him as an ingenious, brazen, indefatigable problem-solver, with forgery and lock-picking as metaphor. “This man has no ticket,” says Molly in the opening minutes of Fitzcarraldo, as she and Brian crash into the lobby of the opera house in Manaus after having rowed for two days and two nights from Iquitos. Yet, insists Molly, Fitzcarraldo has a moral right to enter the auditorium, see his hero Caruso in the flesh, and hear him sing. In this spirit, Herzog believes, the natural order would be disrupted if a misdemeanour didn’t occasionally intrude into the life of a working filmmaker. To help jump the hurdles, he suggests, purloin that which is absolutely necessary. It has always been Werner’s own particular long-term survival strategy.

Over the Rogue weekend, as Herzog responds to his audience, telling story after story from memory, a repository filled with decades of filmmaking tales, this idea becomes ever clearer. I find in my handwritten notes, taken at Rogue in June 2010, the following: “Raphael talks about some rule he broke when filming at Chernobyl. Werner exclaims: ‘That was a very fine and Rogue attitude.’” It might all have something to do with the exquisite Herzog line recorded by Alan Greenberg on the set of Heart of Glass: “There is work to be done, and we will do it well. Outside we will look like gangsters. On the inside we will wear the gowns of priests.” What I can decisively say is that Herzog and the Rogue participants I met have been mutually forgiving of each other, considering the former is wholeheartedly dismissive of traditional film schools, and the latter a self-selected group which, if truly Herzogian in temperament, would gently throw the offer of a place at film school back in their hero’s face.

Rogue – where the emphasis is more on surveying one’s own “inner landscapes” than anything else – is a strong stimulant, the pedagogic equivalent of being doused with ice water. It affirms that Herzog’s stupendous curiosity and love of the world, his explorations into uncharted territory across the planet, his insatiability for inquiry and investigation, his voracious appetite and intensity of belief, his attraction to chaos in its many iterations, have never been stronger. With his makeshift film school, a summation of many years’ work, Werner has seized hold of ideas that appear in interviews stretching back forty years, acknowledged their contemporary relevance, then recalibrated and brushed them down. By doing so, he has left behind previous incarnations. The stalwart of New German Cinema has long been displaced. The accused of any number of Fitzcarraldo controversies is in the past. The director of five features with Klaus Kinski (the last one made more than a quarter of a century ago) is more or less gone. What remains is the resourceful, optimistic filmmaker, still going strong, shepherding us into action, showing us how to outwit the evil forces, leading by example. “I have fortified myself with enough philosophy to cope with anything that’s been thrown at me over the years,” says Herzog. “I always manage to wrestle something from the situation, no matter what.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|