Columbia 1968

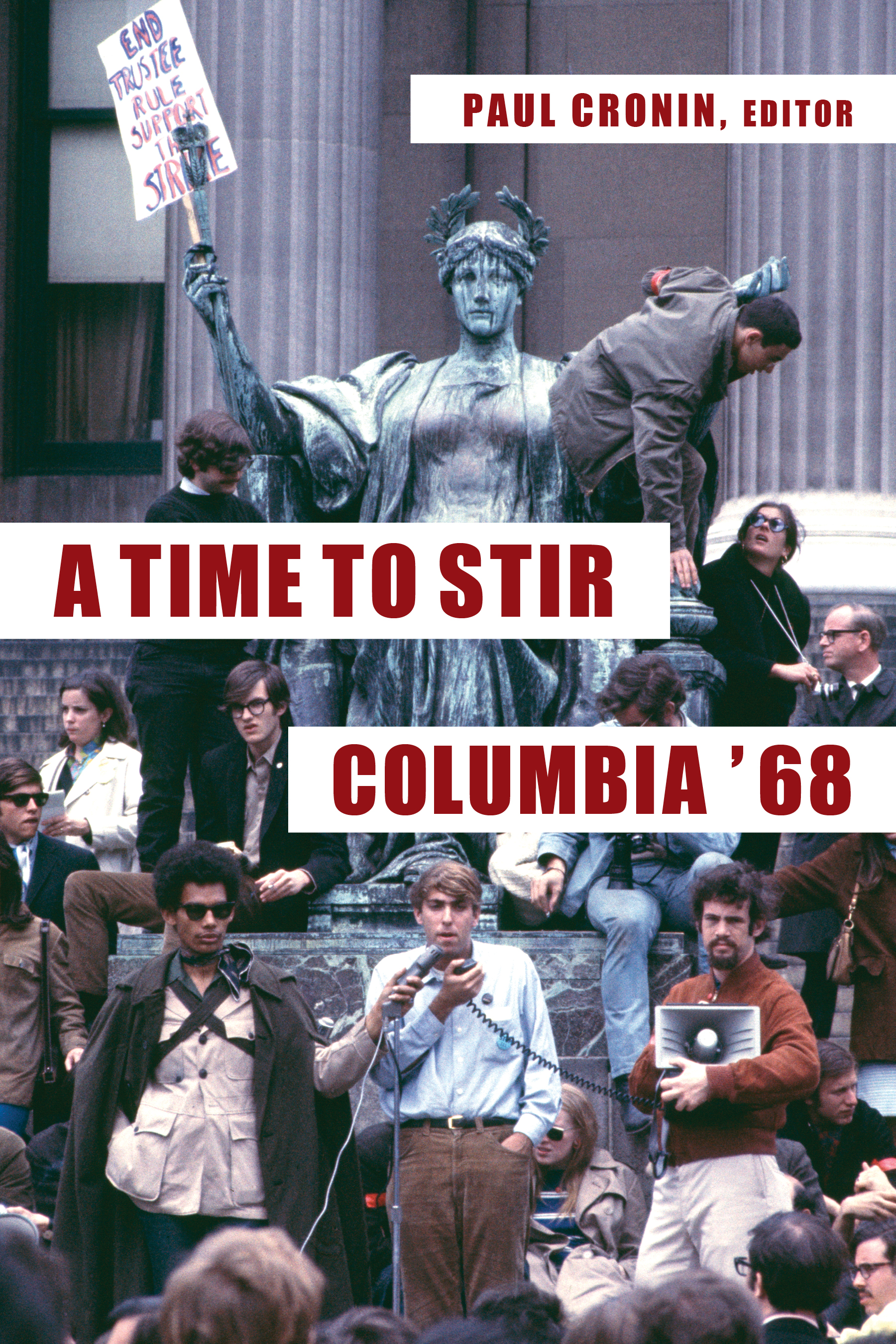

A Time to Stir: Columbia ’68 (2018) edited by Paul Cronin and published by Columbia University Press, contains more than sixty newly written testimonials from a range of participants in the 1968 campus protests at New York’s Columbia University, when two key issues of the era – civil rights and the Vietnam War – collided. A chronology of events here. The book is accompanied by a fifteen-hour illustrated history built from newly filmed interviews, hours of historical footage, and thousands of never-seen photographs. A chapter breakdown is here and a 650-page printed transcript of the complete project is available. An associated film, Columbia EXPERIMENT, is here. A piece of the 1968 trilogy. Various related books in progress, including a volume of photographs, a book of essays, and a three-volume collection of primary documents (Organising, Occupation and Reconstruction) and two of secondary sources (Commentary).

A Time to Stir: Columbia ’68 (2018) edited by Paul Cronin and published by Columbia University Press, contains more than sixty newly written testimonials from a range of participants in the 1968 campus protests at New York’s Columbia University, when two key issues of the era – civil rights and the Vietnam War – collided. A chronology of events here. The book is accompanied by a fifteen-hour illustrated history built from newly filmed interviews, hours of historical footage, and thousands of never-seen photographs. A chapter breakdown is here and a 650-page printed transcript of the complete project is available. An associated film, Columbia EXPERIMENT, is here. A piece of the 1968 trilogy. Various related books in progress, including a volume of photographs, a book of essays, and a three-volume collection of primary documents (Organising, Occupation and Reconstruction) and two of secondary sources (Commentary).

When the country, into which I had just set my foot, was set on fire about my ears,

it was time to stir. It was time for every man to stir.

Thomas Paine

Columbia’s problem is the problem of America in miniature.

Tom Hayden

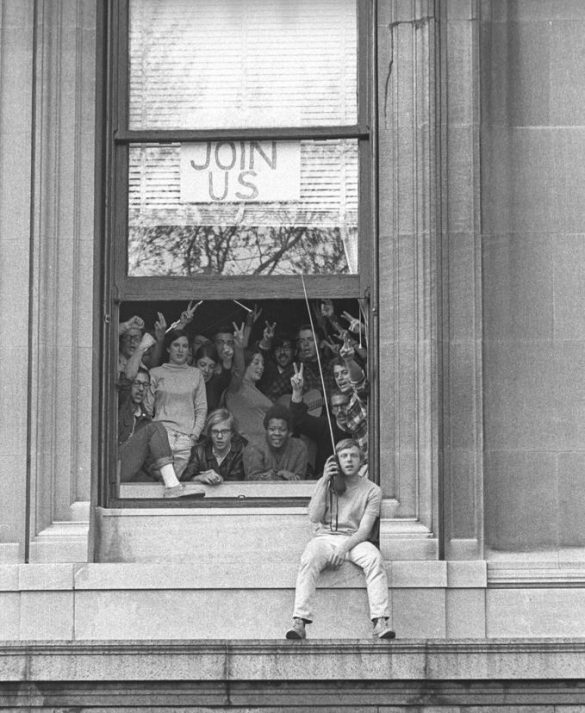

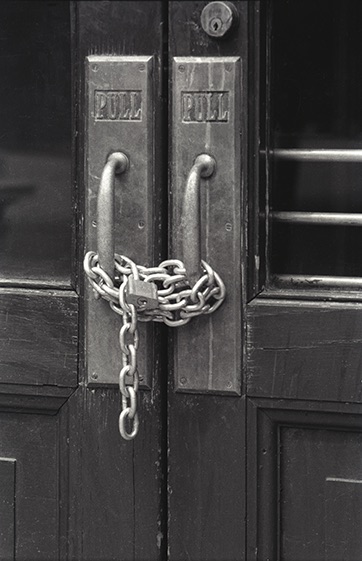

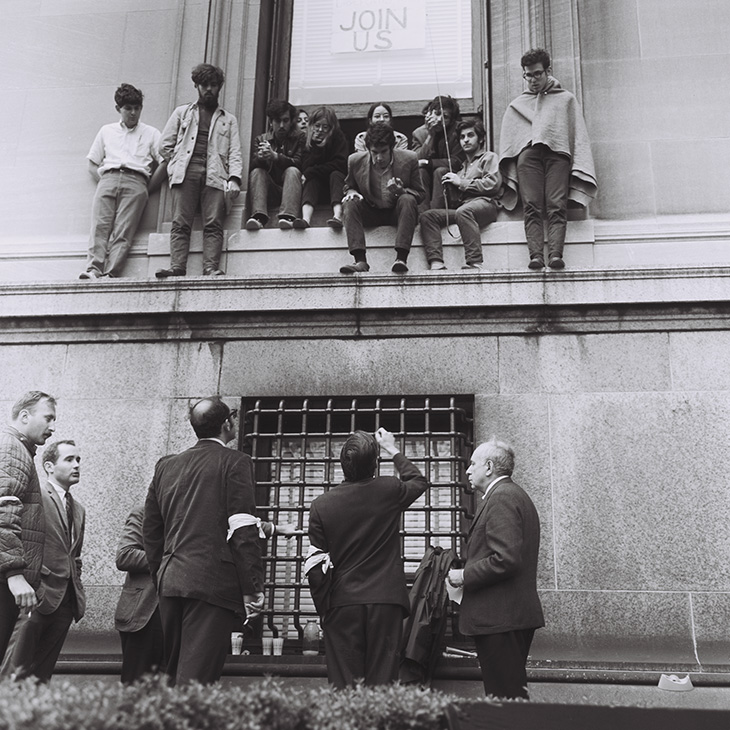

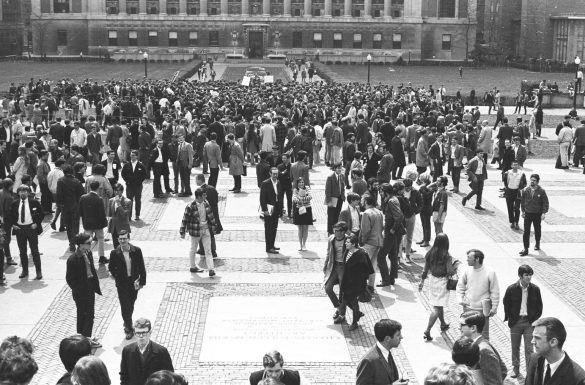

April 1968. Hundreds of emboldened Columbia University students, many allied to two groups – Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and Students’ Afro-American Society (SAS) – take direct action against what they regard as their university’s racist and militaristic policies by barricading themselves inside five buildings on campus. All of them together, behind locked doors, with a unified vision, issuing demands: Columbia must end construction of a gymnasium in nearby Morningside Park (public parkland situated within a primarily black neighborhood – “Gym Crow Must Go!”) and disaffiliate with the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), which is conducting weapons research for the Department of Defense and so connects Columbia to war in Vietnam.

Immediately are opened up, and made crystal clear, the schisms that have long existed on campus. As Columbia’s unresponsive administration – controlled by businessmen-trustees and overseen by a dithering president – attempts to defuse the situation, as faculty meet and discuss the issues, as undergraduates opposed to the occupiers mobilize a raging reaction to their classmates’ rebellion, hundreds of New York police officers are assembling. After six days, with neither side leaning toward compromise, with no hope of reconciliation, law enforcement remove the protesters – more than seven hundred, of whom nearly two hundred are not Columbia students – from their makeshift, self-governing communes, one of which is held exclusively by black students. The “bust” has a clarifying effect on many who otherwise would have paid little attention to the world of politics around them. Students who had sidestepped the protests, who never would have thought of involving themselves in disruption of any kind, are galvanized, and a fresh wave of turmoil surges across Columbia, helping to set in motion similar actions at colleges and universities – public, private, rural, urban – across the United States.

The social and political issues that had energized the campus and the student protest movement for years reflected a formidable and transformative populist uprising that was engulfing whole swathes of the nation, even the globe – a rejoinder to the perceived inadequacies of mainstream institutions and politics. By 1968, in the shadow of a war that was pulling in hundreds of thousands of young American men, and only three weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Columbia University – so close to the center of the world’s media industries and even closer to the African American community of West Harlem – became one place where the academy’s plight during the Vietnam quagmire, and the culture wars of the era, were conspicuously played out.

The social and political issues that had energized the campus and the student protest movement for years reflected a formidable and transformative populist uprising that was engulfing whole swathes of the nation, even the globe – a rejoinder to the perceived inadequacies of mainstream institutions and politics. By 1968, in the shadow of a war that was pulling in hundreds of thousands of young American men, and only three weeks after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Columbia University – so close to the center of the world’s media industries and even closer to the African American community of West Harlem – became one place where the academy’s plight during the Vietnam quagmire, and the culture wars of the era, were conspicuously played out.

At the core of any Columbia ’68 narrative must be the students behind the inciting incident, to whom everyone else responded. In their stories, we learn about the disillusionment of male undergraduates at Columbia College, the pent-up frustrations, the persistent and earnest activism, and the spontaneous occupation of five buildings by what student leader Mark Rudd described as a “motley mob.” Here was a ragtag collection of disaffected constituencies, a crowd – passionate, polemical, and reliant on instinct—with diverse political commitments but commonality of purpose, brought together by circumstance and a series of improvisational encounters, with a more or less group-centered leadership.

Each occupied building quickly developed its own personality, drawing in a particular kind of activist. Low, Avery, Mathematics, and Fayerweather became dynamic enclaves packed with hundreds of undergraduates and graduate students, holed up side-by-side with a host of sympathetic outsiders who suspected that Columbia would prove fertile recruiting ground for action on the streets beyond campus. Of vital importance, too often forgotten today, or more likely simply unknown, was the fact that Hamilton Hall was held by a group of contemplative, disciplined black Columbia students who proved to be the strategic and moral centrifuge of the protests. For these men and women, pledged to the ideal of self-determination, some enthralled by the rise of Black Power, the act of closing ranks was made easier by the fact that most already knew each other. Initially suspect of the level of commitment of white students, and with practical support offered by Harlem locals, these black students were, from the start, on a different trajectory than the other protesters.

Every individual on the Columbia campus in 1968 – no matter whose company they sought or kept, which organization or ideology they aligned themselves with, how committed they were to allegiances, or how fiercely they vowed to remain unaffiliated – was motivated by different reasons. With the enduring absence of a monolithic student bloc, with pulses beating ever faster and a stunning lack of stability to the situation, with rival factions proliferating by the day, consensus and conciliation would never be easy to reach. There wasn’t a groupuscule that was not, at one time or other, at odds with every other groupuscule. This was a contest of ideas, a confluence of mismatched concerns making for an extraordinarily stimulating learning curve that no one had ever before experienced. Whether aware of it or not, everyone active in the protests was showing one another, once the textbooks were put away and the classroom doors were sealed, how living through a historical moment could be an educational windfall, a potent form of vivification.

The tumult had been brewing for years. Study Columbia’s student newspaper Spectator from 1965 onward and read about a centralized administration offering paper-thin promises and desperate to prevent dissent from upsetting its fund-raising efforts, alongside a marked acceleration of student protest and voice-raising, a drive toward transgression and extreme measures, the jettisoning of complacency, and the censuring of conformity: an expanding number of single-issue political groups operating on campus; provocative antiwar gatherings around New York involving Columbia students; the steady, sometimes reluctant abandonment of conventional, moderate tactics as seen through increasingly contentious campus rallies, including protests against the Reserve Officer Training Corps and recruitment by the Central Intelligence Agency and the Marines Corps; students involving themselves in community outreach in Harlem; civil rights activism and furor over the draft, and the prospect of conscription and the brutality of the Vietnam body count; demonstrations at the site of Columbia’s proposed gymnasium; heated student and faculty responses to the university’s heavy-handed purchasing of neighborhood buildings and subsequent evictions; and picketing at Columbia dining halls in support of better conditions for its workers. Each of these actions fueled the next. Worried about your grades? About being thrown out of Columbia? Consequences, be damned!

[transcript of Organising vs. Activism by Mark Rudd here]

By 1968, it was clear that students were becoming a vital and effective political force and that inflexible university administrators across the nation would be unwise to ignore calls for change. Demands from students to become part of the decision-making processes were thunderous, with “relevance” a new watchword when it came to curriculum reform. But change could come only if workable channels of communications and possibilities for meaningful dialogue existed, and many vocal students felt that those who ruled Columbia had constructed a paternalistic, archaic culture of opaqueness. In October 1965, David Truman, dean of Columbia College, spoke to an interviewer about student civil disobedience, declaring that “the circumstances under which such protest would be acceptable are extremely rare.” As with Berkeley in 1964, the battleground became one of free speech. On the first day of the fall 1967 semester, in an attempt to stave off disruption, a ban on protest inside campus buildings was instituted.

Columbia students were part of a cohort of headstrong youngsters immersed in a set of subcultures that by 1968 had permeated deeply and were helping to cultivate in millions of people a sense of personal responsibility for institutional behavior. Many of them, for the first time in their lives, saw the necessity for direct action. This may have been a coterie of ludic, hedonistic hipsters who gravitated to subterranean downtown festivities, smoked dope and hung out in cafés, or just lingered in dorm rooms sprinkled with psychedelia and burning incense. But there was a counterpoint: this was also a nucleus of sincere, bookish students who just as often could be found at the uptown end of the 1 train, standing on the sundial at the center of the Columbia campus, drawing in fellow students with precocious analyses of world affairs and leftist politics, fastidiously recounting frank historical narratives largely unavailable in the mainstream press, deflecting criticisms and fielding questions. Some of them, like their Berkeley ’64 compatriots, had gone South to assist civil rights organizations with voter registration and educational programs. Others – too young for that – had been taken by parents to the nation’s capital in August 1963 to hear Martin Luther King, Jr. enthrall the nation. Some were classic red (or pink) diaper babies, or children of devoted New Deal Democrats. A few had parents who had suffered under McCarthy or were survivors of the European Holocaust, still so fresh in mind. Some had cousins who had fought in Spain, who had copies of Paul Goodman, David Riesman, and C. Wright Mills about the place, who subscribed to the National Guardian or the muckraking I.F. Stone’s Weekly, that warehouse of subversion. This was, all in all, by 1968, a hyperpoliticized group, indelibly influenced and schooled by television imagery of Operation Rolling Thunder’s jungle war and Bull Connor’s dogs, plus the duck-and-cover absurdity of mutually assured destruction. These rapturous, sloganeering students were swept up into the whirlwind, inflamed by a feverish, idealistic conviction that the hour for action had arrived.

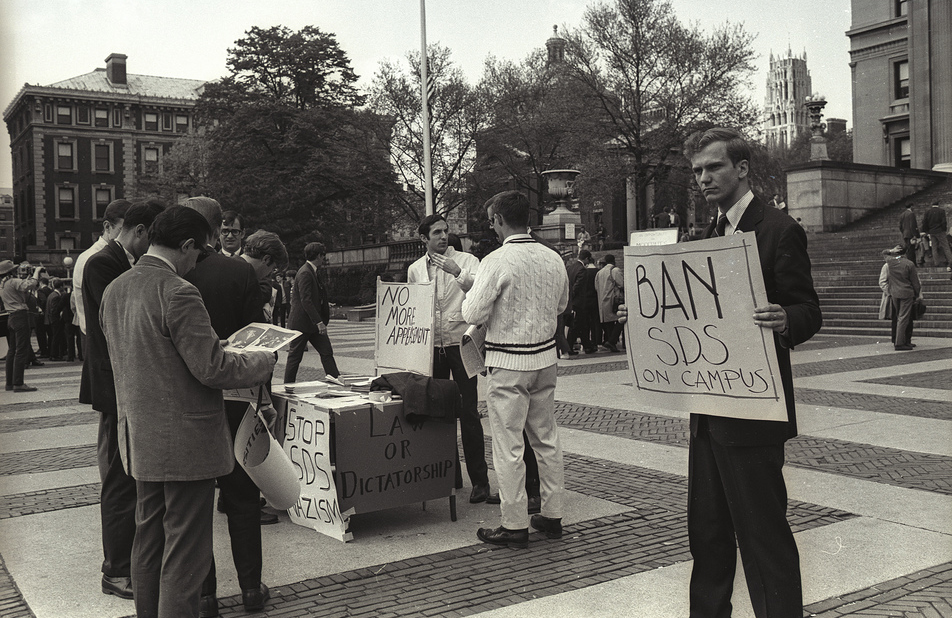

Behind the brick walls of the campus, inside the occupied buildings, some kind of conversion experience was occurring, with great leaps of faith being taken, with boundaries being dissolved, the negation of alienation finally, if temporarily, achievable. The challenges came from all directions, including a battalion of Columbia students who declared that the occupiers’ tactics were an affront to the intellectual spirit of the university. Anxious to show the world that another face of Columbia existed, counterprotesters were determined to neutralize the infectious, invasive demonstrations by retaliating against the mobocracy and marching feet around them. These short-haired, suit-and-tied athletes (the “jocks”) weren’t necessarily opposed to the final aims and long-range goals of the protesters (the “pukes”), who had immobilized the campus and shut down classes, but would have preferred, at the very least, that some form of rational persuasion be practiced instead. “There shall be no use of coercion, disruption, or blackmail to influence the future of this great academic institution,” read a flyer produced by a coalition of groups worried about escalating violence on campus and – staggered by the Columbia administration’s inaction – progressively ready to take matters into their own hands. “Numbers and reason – not force and emotionalism – shall decide.”

Behind the brick walls of the campus, inside the occupied buildings, some kind of conversion experience was occurring, with great leaps of faith being taken, with boundaries being dissolved, the negation of alienation finally, if temporarily, achievable. The challenges came from all directions, including a battalion of Columbia students who declared that the occupiers’ tactics were an affront to the intellectual spirit of the university. Anxious to show the world that another face of Columbia existed, counterprotesters were determined to neutralize the infectious, invasive demonstrations by retaliating against the mobocracy and marching feet around them. These short-haired, suit-and-tied athletes (the “jocks”) weren’t necessarily opposed to the final aims and long-range goals of the protesters (the “pukes”), who had immobilized the campus and shut down classes, but would have preferred, at the very least, that some form of rational persuasion be practiced instead. “There shall be no use of coercion, disruption, or blackmail to influence the future of this great academic institution,” read a flyer produced by a coalition of groups worried about escalating violence on campus and – staggered by the Columbia administration’s inaction – progressively ready to take matters into their own hands. “Numbers and reason – not force and emotionalism – shall decide.”

The largest mass of students, those cautious tenderfoots, stood on the sidelines, struggling to understand precisely what was going on, but knowing enough that they couldn’t let this historic moment pass them by. Through the maelstrom stumbled an incredulous, outdated, and painfully vulnerable university administration, ill equipped for the problem-solving tasks with which it suddenly was faced, accused of having its reputation tarnished by incestuous connections with the New York power elite and, more broadly, the nation’s establishment matrix. Foot soldiers from the mainstream media and the underground press congregated on campus, cameras rolling and typewriters at the ready, transforming a few square blocks of Morningside Heights into a fishbowl for the entire world to stare into. They installed themselves wherever the New York Police Department (NYPD) and clutches of concerned parents – bearing chicken soup and bail money – weren’t taking up space.

It might be said that the efforts of most everyone at Columbia during those days were both legitimate and inappropriate, that everyone conducted themselves both honorably and improperly. To be sure, everyone made mistakes. The faculty, for example – only a small number of whom would have considered themselves radical – advanced itself as an honest broker but immediately lost its footing, revealing just how powerless it really was, and for the most part refused to take a genuine political stance. Almost overnight, liberal professors – convinced that the campus was a sanctuary to be protected at all costs – became, in the mind of radical students, a lost cause. Some, who had long been identified as progressive, were overtaken by events and, like their hardline colleagues, found themselves dubbed reactionary dinosaurs. As Columbia professor of French Richard Greeman explained in a 1968 essay, faculty sympathetic to the aims of the student dissidents but who considered their tactics “coercive” were hypocrites and cowards. These people, wrote Greeman, “would never have dared to consider taking a position on the gym, of which they all disapproved, had it not been for the mass student pressure from below expressed through direct action.”

That pressure came most vehemently from adaptive, swaggering twenty-year-old rebels who were learning as they went along – a bullheaded sliver of whom were drawn to the Bolshevik notion of the vanguard and the heroic guerrilla Che’s foco theory, to the cadre’s leadership of an armed insurrection. (“That’s out of date,” aspiring Columbia SDSers were being told by 1968 of the Port Huron Statement, the organization’s relatively placid and reformist Jeffersonian founding document, issued six years earlier. “We’re reading Lenin’s The State and Revolution and Che’s speeches by now.”) The activities of these agitators – who had little regard for the potentially damaging consequences of their strategy – ran counter to the antihierarchical participatory democracy that blossomed amid the often joyous, sensual atmosphere of the occupied buildings. The restructuring of the university, for example – which in the months that followed became a focus of graduate student groups – was deemed by them a hopeless and co-optive act. Some firebrands were intent on turning the campus into little more than the staging ground for their revolutionary aims, and it is no surprise that a direct line can be drawn from Columbia ’68 to the infamy of Weatherman. Years later, novelist and Mathematics occupier Paul Auster wrote that 1968 was the year he went “crazy.” A Time to Stir suggests that the real story isn’t what the tribe did once they reached that frenzied state, but how they became crazy.

However one feels about what happened at Columbia University in 1968, the events serve as a rich case study, an opportunity to investigate broad themes, all not only relevant to campus events but also emblematic issues of the late sixties.

The Role and Responsibility of Democratic Citizenship

Throughout American history, citizens have used a variety of means—political organizations, voluntary associations, journals of opinion, public rallies, and protests – to exercise their democratic rights and make political and policy preferences known to elected officials. Few periods of American history were as fecund (and chaotic) with such revitalizing expressions of citizen activism as the sixties, especially in terms of the creation and use of grassroots democratic tools, most prominently in the form of social change movements – often led by those feeling marginalized by mainstream politics. In 1960, Columbia professor Daniel Bell noted in his The End of Ideology that “one can have causes and passions only when one knows against whom to fight,” before asking: “Today, intellectually and emotionally, who is the enemy that one can fight?” By the end of the decade, for some students at Columbia University, with their heightened consciousness and lists of interlocking grievances, that question was all too easy to answer. The year 1968 tested the seams of the American quilt like no other, and the deluge of antiwar protests and student activism in the second half of the sixties is a significant chapter in the story of postwar democratic inventiveness and effectiveness. Fundamental questions were raised about the citizen’s ethical responsibility to counter laws and politics considered unjust or illegal. Inequitable mandates needed to be defied. Where previously apathy was the standard, dissent thrived. Dissent became protest, from protest to resistance, resistance was overtaken by confrontation, and then confrontation jumped to militancy. The range of strategies employed by students to facilitate change on campus and beyond represented a vivid challenge to the assumption that authorities should be respected without question. Disruptive insurgency ruled the day. There would be no business as usual.

In his 2016 obituary for human rights attorney and activist Michael Ratner, one of the few Columbia Law School students who plunged into the protests of 1968, David Cole wrote: “Ratner knew that when you sue the powerful, you will often lose. But he also understood that such suits could prompt political action, and that advocacy inspired by a lawsuit was often more important in achieving justice than the litigation itself.” These lines replay an idea expressed as early as June 1968 in Ramparts magazine: “Columbia was no revolution because those who created it could never really hope to take power.” Students went straight to the heart of a mighty university, one backed by New York’s legal, political, and media power industries. Armed with little more than slingshots, many figured it likely would be an impossible fight, even with a global spirit of rebellion behind them, even when in solidarity with compadres on other continents. But at Columbia in April and May 1968, a prototype operation was presented to the world. Within days of the events, newspapers reported copycat happenings across the country.

Given that plans for the gymnasium needed to be abandoned and Columbia’s disaffiliation from the IDA was a non-negotiable issue, students felt that they were committing a justified act of nonviolent civil disobedience. Needless to say, some saw it differently, urging that the occupations upset the rightful order of institutional procedure and jeopardized the university’s special status as a much-needed enclave set apart from politics, war-making, and the like. What happened to the campus as a bastion for the steady maintenance of basic notions and practices of academic freedom? What good could ever come from shutting down a university and inflicting upon it a potentially mortal wound? Richard Nixon, declaiming against anarchy and stumping for law and order, trumpeted Columbia ’68 as the first volley in attempts by a lunatic fringe to seize control of the nation’s campuses, while J. Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation used the events as a pretext to go after New Left organizations with added fervor.

Michael Neumann, in his contribution to this collection of essays, writes that what the campus protests might have achieved beyond the boundaries of Morningside Heights is scarcely worth thinking about. His trenchant case against Columbia ’68 begins with accusations that the insular, self-satisfied protesters, relishing the carnivalesque atmosphere, were more involved with “therapeutic” self-expression than any kind of meaningful political activity. Todd Gitlin famously noted that “[w]hile the Right was occupying the heights of the political system, the assemblage of groups identified with the Left were marching on the English department.” The gym and the IDA were, of course, to a certain extent only pretexts, a spur to action. Yet the symbolic value of the protests – “bringing the war home” – was pivotal. Symbolism, writes Eleanor Stein in this book, “is an enormously important, motivating, inspiring and engaging aspect of human existence and life.” Such debate frames one of the central issues of A Time to Stir: what is it that constitutes legitimate and effective political action – especially when it emerges from the ground up, from those with limited power?

The Role of the University in American Society

In the final years of the sixties, Columbia University displayed in crisp focus the crisis of the liberal academy amid the cultural, racial, and political dramas of the time. Of protesting students, renowned historian and Columbia history professor Richard Hofstadter noted in 1968 that “to imagine that the best way to change a social order is to start by assaulting its most accessible centers of thought and study and criticism is not only to show a complete disregard for the intrinsic character of the university but also to develop a curiously self-destructive strategy for social change.”

But for Columbia students, what better place to vent their anger? The doctrine of academic freedom prevented the university administration from openly opposing the pointless war being waged in Vietnan, even while many of its faculty and students – as well as President Grayson Kirk and Vice President David Truman – did so with mounting conviction. More troubling was that several faculty members were consultants for the IDA, on the board of which Columbia’s president served, thus giving the university an appearance of connivance with the war. Students saw this as a sign of hypocrisy, the worst marker of academic complicity in the military chain of command. At the same time, Columbia’s practical need for space and expanded facilities resulted in a land grab from a public park in West Harlem, an eerie echo to the kinds of thefts of property and persons familiar in previous centuries. What better indication than a vast gymnasium with a symbolically segregationist back door did anyone need to understand that Columbia – expected to have an evolved, even enlightened approach to racial politics and the interaction between town and gown – was so shamefully out of step with the era? The gym proved to be just one element of the university’s nefarious, exclusionary dealings in Morningside Heights, with its sanitization of the neighborhood and removal of undesirables from newly purchased residential buildings.

More generally, after the Free Speech protests at Berkeley in 1964, students’ realization of themselves as cogs in a faceless bureaucratic system, as personnel to be molded, became increasingly ubiquitous. This stoked the anomie and resistance of its young charges, sullying the notion of Columbia as a virtuous community of scholars. For many students, Columbia – though smaller than public universities, such as Berkeley, the size of which encouraged protest on a larger scale – did not provide the cohesive, collegiate experience that its status in the Ivy League seemed to promise. As the Report of the President’s Commission on Campus Unrest stated in 1970, too many faculty appeared to the average freshman “more like corporation executives than cloistered scholars,” more committed to academic training that prepared students to fit the requirements of Cold War militarism than anything else. Disenchanted, with an unhappy understanding of the coercive university as an embodiment of the outside world, these youngsters had been steadily disabused of the notion that the ivory tower was a neutral entity, able to keep its hands clean of the Vietnam War and institutional racism. As Columbia student radical David Gilbert wrote in 1968, the structures of American higher education were “dedicated to the social functions required by modern capitalism.”

These issues were exacerbated for students of color, with the university’s handful of black students resentful of a distant, unresponsive, and overwhelmingly white institution. Columbia’s Core Curriculum – requiring undergraduates to study classics in Western civilization’s literary and philosophical heritage – was for some an oppressive celebration of imperialist values. Recent acknowledgments by antebellum universities of their participation in the slave trade have generated a new and robust reckoning with how intimately and interwoven the academy was with systemic oppression.

Racial Justice in Sixties America

Three weeks before Columbia students occupied the campus, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, setting in motion a furious, grief-stricken response throughout the nation’s urban communities that lead to many deaths. King’s murder contributed to a decisive shift within the civil rights movement – from nonviolence and peaceful self-defense to Black Power, a militant demand for black freedom. These changes manifested themselves at Columbia in early 1968 with a change in SAS leadership, and then, after the joint SDS–SAS rally and sit-in at Hamilton Hall – that poignant, if brief, flash of interracial solidarity – with SAS telling white Columbia students they had to depart Hamilton and hold their own building. This segregationist move recapitulated the wider struggle and mimicked larger structures, as articulated by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In a 1966 statement, SNCC explained that “white people who desire change in this country should go where that problem (of racism) is most manifest.” Reflecting the call for white activists to leave the South and head home to the urban North, before dawn on April 24 protesting white Columbia students – accused of indecision, feeling rejected and down-heartened – departed Hamilton, as requested by their black comrades. The doors barricaded behind them, this small group moved across campus and smashed their way into the president’s office in Low Memorial Library, the university’s main administrative building. The “community of common commitment” was still there, but a new chapter in the fragile alliance between blacks and whites at Columbia was beginning.

Hamilton Hall remained “black only” for the rest of the weeklong occupation, under the leadership of SAS, which asserted that above all it represented the interests of Harlem’s working-class community. The entrance into Hamilton of Stokely Carmichael (former SNCC chairman) and H. Rap Brown (current SNCC chairman) on April 26 linked Columbia to a wider spectrum of societal concerns. Whether or not white SDSers were aware of it at the time, SAS’ control of Hamilton provided the basis for the sustained occupation of not just that building, but the four others too, primarily because the NYPD were fearful of how Harlem might respond if they moved in to clear the campus. As such, the importance of Hamilton (renamed by students “Malcolm X Hall”) cannot be overstated. By closing ranks the way they did – efficiently, peaceably – its inhabitants demonstrated that Black Power ideology wasn’t necessarily the incendiary polar opposite of the civil rights movement. Instead, when put into practice, its approach represented a carefully structured and restrained operation, displaying tactical skill and moral fortitude. The black students’ actions were made all the more compelling when one considers the risks they were taking in invading private property of the rich and powerful. For white students, there were likely to be few serious negative repercussions and especially no threat to life and limb. For African Americans, who could not expect such a soft landing and for whom the recent killings in February 1968 of three black students at Orangeburg, South Carolina, reverberated far more strongly, the situation was different. Unlike some white students, they saw no nobility in being arrested and beaten up – or worse. Juan Gonzalez recalls in interviews that within hours of the occupation of Hamilton Hall, he saw guns inside the building, brought in by Harlemites determined to prevent any overreaction by the authorities.

Participatory Democracy

Even as the United States has been a dynamic society whose promise of equality, liberty, and freedom of expression has offered the American people great opportunity, those same values have also produced intense social tension. Time and again, citizens have wrestled with the need for change. In the sixties, the conflict between those who advocated rapid, even radical, adjustment and those committed to traditional ideas of political and social order was made manifest across the country – from small-town politics to national debate, from inner cities to remote academic enclaves.

Columbia University was a focal point for that contest, one of the sites where a new radical activism was emerging. The self-rule that developed within the optimism of the occupied buildings, filled with people who envisioned a society in which citizens would fully share in the decisions shaping their lives, was a memorable reflection of Thoreau’s call: “Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence.” It was truly a mass movement – enmeshed in situations of unusual turmoil, fluidity, and, occasionally, histrionics – that shook Columbia’s foundations, even if the media threw up Mark Rudd as antihero of the hour, and even if a number of protesters clearly moved beyond tactics that were perceived by most as strategically acceptable.

By 1968 at Columbia, influence had flowed into the hands of a small group of voluble and well-read (Mao, Debray, Gramsci, Fanon) SDSers whose approach differed markedly from traditional nonviolent New Left ideology. With long-range goals, and feeling betrayed by spineless liberalism, they had been, by 1968, engaged in years of political activity and “base-building” – via strategizing, dorm canvassing, teach-ins, meetings and rallies, and the writing and distribution of petitions and broadsides. Once the five buildings were taken and everyone knew the NYPD would soon be arriving, with the media spectacle swelling (day after day the protesters were demonized on the front page of the New York Times), these advocates were somehow in the pilot’s seat, at least to the extent that they were able to set a context and wield influence for three or four days. This small faction believed it could be the single force – the spark – capable of igniting a powerful revolutionary spirit, and that, in response, the power of the state, through a violent police action, would reveal itself, thus pulling off the fence all those previously unresponsive to SDS appeals.

The authoritarianism that marked this tiny minority of protesters meant they clashed with many inside the buildings and were accused of practicing “manipulatory democracy.” Note the essay in this book by Joshua Rubenstein who, while inside Fayerweather, confronted – and resisted – what he felt were SDS strong-arm tactics. Contributions from Nancy Biberman and Carolyn Rusti Eisenberg are revealing in different ways, as they touch on SDS’s macho, unegalitarian tendencies, with its treatment of women, in the years – months, even – before the full power of the women’s movement took hold. According to a common line from female interviewees on their experiences of the occupation, “the men told us they had important work to do and that we should go make sandwiches.” The emancipation of female Barnard college students did not begin inside Fayerweather Hall, yet looking back, both women and men of the movement acknowledge that the seeds of consciousness were starting to take root.

In his book about Berkeley Free Speech Movement activist Mario Savio, Robert Cohen writes of the historicizing of the New Left, the suggestion of some scholars and activists that the movement’s “approach to grassroots organizing” during its early years was “democratic, nonviolent, undogmatic, and innovative.” This phase is followed by an implosive, irrevocable period of “alienation, cynicism, and revolutionary fantasies.” Other (mostly younger) historians, adds Cohen, see the historical progression differently, proposing that alongside the sectarianism that split apart SDS came mass protests that “surged on the campuses.” Within the context of what is today known as the “good sixties–bad sixties” interpretation, Columbia ’68 can be looked on as a temporal hinge, the moment when the tone darkened and, for some, revolutionary fantasies became more harmful than anything else. At the same time, while the hothead Morningside Heights revolutionaries always shouted the loudest, they were only ever a small proportion of the protest movement, one that grew in pragmatic strength, both on and off campus, following the bombing of Cambodia and the killings at Kent State.

What of the protesters today? What came next? Although for some participants there was certainly a performative, apolitical aspect to time inside the buildings, for many, the rebellion signaled a shift of priorities that sent them down a path of social engagement they have been walking ever since. As Thomas Paine wrote of “panics”: they might last only a short time, but “the mind soon grows through them, and acquires a firmer habit than before.”

The late Allan Silver, a Columbia sociology professor who fumed against the protesters, insisting that they had “violated basic rules,” also described his best students of those years (including Ted Gold, killed in 1970 when a bomb he and colleagues were making in a Greenwich Village townhouse accidentally exploded) as among “the most incandescently brilliant” he had ever taught. Look at student publications from the period, as well as the many flyers and handouts produced, and note the sophistication of written material produced by twenty-year-olds. Beyond their obviously fierce intelligence, this is a group that has long estranged itself from apathy and inertia. To this day, many of the campus protesters remain politically ambitious, committed to social change, and have, in their own ways, continued to practice Marcuse’s liberating Great Refusal. One hears all too often about the sixties radical-turned-company man (the “Jerry Rubin syndrome”). But take a cross section of the most active Columbia protesters and today find a group of committed retirees, still suffused by the consciousness-raising energy of the sixties. Unlike so many youthful protesters in 1968, today’s activists have a generation (or two) of knowledgeable, contrarian grandparents (often networked together, still challenging the status quo) to call on for guidance and counsel when it comes to facing any number of travails – political and otherwise. Given the exigencies of raising children and paying the mortgage, to say nothing of the predicaments of old age, a certain level of engagement has inevitably slipped away. But as we come face to face with new threats and embark on our own epochal battles, these folks can school us in how to confront the long odds and hard knocks, to help us understand our shared experiences. They are available to tutor us out of quiescence, to show us how to build up the spirit, and to stave off discouragement, as one obstacle morphs into the next.

[transcript of 1968: End of an Era here]

Among the veterans of the Avery commune (the School of Architecture) who I interviewed, for example, are no billionaire property developers, instead only socially conscious designers, urban planners, and community developers. In his Gates of Eden: American Culture in the Sixties, Morris Dickstein (an assistant professor of English at Columbia in 1968) wrote of the twentieth-anniversary celebrations of 1968, a campus meeting of strike veterans. For Dickstein, “it was remarkable how many had somehow remained true to their ideas… Few, it seems, had just gone for the money, despite the Gilded Age ethics of the Reagan years. It was clear that some sense of community responsibility would continue to shape the remainder of their lives.” And indeed it has, something I can attest to, having caught up with many hundreds of Columbia’s protest veterans – public servants, doctors, teachers, academics, writers – some thirty years after Dickstein. Mark Rudd, these days working as intensely and urgently as he was five decades ago, has, over the years, been an especially important presence for me. An energetic, compassionate rabble-rouser, currently training young leadership in strategic organizing and how to build structures and create definitive outcomes that will carry the movement forward in New Mexico (where he has has lived for forty years), generations into the future, Mark is today anxious to let it be known what mistakes were made. “Out of Columbia came the belief that militancy will do everything,” he explained in a 2007 interview with me. “We happened to be lucky at that moment. There had been base-building and politicization of the campus, years of education, confrontation and agitation, and years of talking with people. It was real organizing that went on. But coming out of Columbia it was our militancy that we seized on. We thought that militancy could become a strategy, when really it’s only a tactic which sometimes, occasionally, if you’re lucky, works.” The young leadership of Columbia SDS was hoping not just to understand the world, but to change it – by any means necessary. Base-building and long-term organizational strategies were seen as of secondary importance.

As the scope of the essays that follow shows, the uprising at Columbia University can be understood through many perspectives and stories. There is no one narrative, but many. All can be considered, however, in one common and vital way: as a microcosm of the nation’s wider concerns. There remain, of course, at least as many avenues open for exploration, including those that tackle post-1968 Columbia. The university was changed forever, most immediately with the imperious, prideful President Grayson Kirk – who in April 1968 described the young people of America as having “taken refuge in a turbulent and inchoate nihilism” – and Vice President David Truman both dethroned; the Columbia Senate (“a policy-making and legislative body with full jurisdiction and power to deal with all matters of University-wide concern”) established the following year; the revision of disciplinary procedures implemented (including the dissolution of the more patronizing elements of in loco parentis); and the hiring of more black faculty, including Charles Hamilton in the government department.

By documenting the story of a generation of politically committed citizens who came of age in a world painfully out of equilibrium and who sought to reshape that world, A Time to Stir has the potential to deepen our understanding not just of the widespread social unrest that pervaded the final years of the sixties in the United States and beyond, but also the theory and practice of contemporary protest and debate. The year 1968 was the high point of an era when the fight between those who advocated rapid adjustment of norms and values and those who were committed to maintaining traditional ideas of political and social order erupted in every direction. To delve into the campus events of that year means to explore an array of ideas, ideologies, histories, disputes, groups, and individuals, and so let loose a range of themes that are unmistakably as germane and worthy of investigation today as they were all those years ago. Every significant beat of this story finds an contemporary analog at least as pertinent today as it was five decades ago. We ignore these resilient problems, these present-day struggles, these issues and fundamental questions of culture, politics, and society, at our peril. Motivated by an intention to put forth a description of historic events, to fuse the skirmishes of 1968 to the present day, adventuresome readers are challenged to ask themselves: what would I have done fifty years ago?

A version of this essay appears in A Time to Stir: Columbia ’68.