Dramatic Construction

One of the dilemmas is that many students feel that there is some secret set

of rules to follow, and if you follow them you get it right, and they get angry

with you because you won’t give them the rules. Well, there are no rules.

There never were and there never will be, because each circumstance is

different and each director works entirely differently.

Alexander Mackendrick

The thousand techniques are inferior to the one Principle.

David Mamet

(quoting a jiu-jitsu master)

Theorists have been explaining the principles of dramatic construction (and, by so doing, making sweeping generalisations) for many hundreds of years. They have also been applying their ideas to cinema for about as long as the business of filmmaking has been in existence. There’s good reason for this emphasis on storytelling. As master director Akira Kurosawa explained in his autobiography, “With a good script a good director can produce a masterpiece; with the same script a mediocre director can make a passable film. But with a bad script even a good director can’t possibly make a good film.”

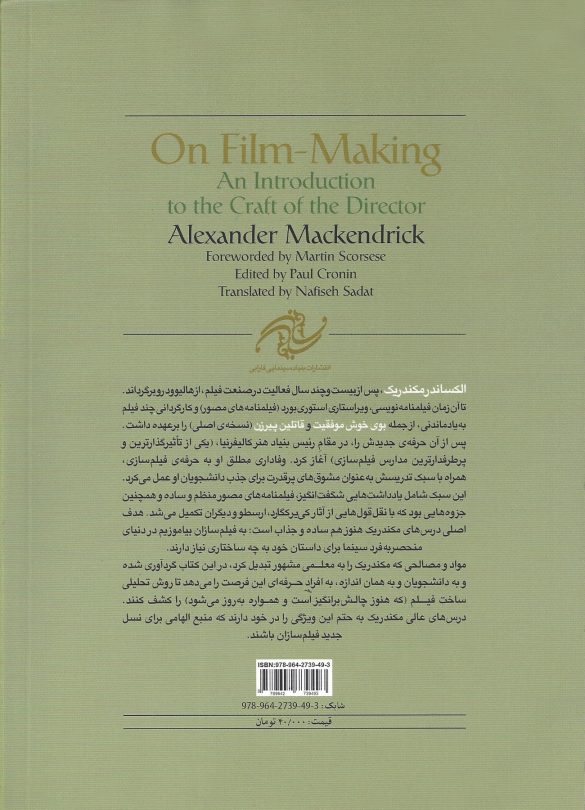

Several books on the subject of classical dramatic construction were of particular interest to Mackendrick, texts he urged his students in the film school of the California Institute of the Arts, where he taught for nearly a quarter century, to read. Representing not just the antedecdents to Mackendrick’s own ideas, as articulated in his book On Film-Making: An Introduction to the Craft of the Director, they are vital to our understanding of how cinematic stories are told. In chronological order:

Aristotle’s Poetics (c. 335 BC)

William Archer’s Play-Making: A Manual of Craftmanship (1912)

Lajos Egri’s The Art of Dramatic Writing (1946)

John Howard Lawson’s Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting (1949)

Aristotle (384 BC – 322 BC) was a Greek philosopher, author of texts on a startling range of subjects. John Howard Lawson writes: “Aristotle, the encyclopedist of the ancient world, has exercised a vast influence on human thought. But in no field of thought has his domination been so complete and so unchallenged as in dramatic theory. What remains to us of Poetics is only a fragment; but even in its fragmentary form Aristotle’s statement of the laws of play-writing is remarkable for its precision and breadth.” Kenneth McLeish agrees: “The appeal of Poetics is partly for the pithiness and mind-expanding nature of its pronouncements.” Today we are surrounded by many different ways of representing/imitating reality. An extraordinary array of styles and techniques, media and forms, are available to us. Aristotle’s ideas are just one way of doing things, and for anyone intrigued by the orderly “beginning, middle and end” arrangement of story, Poetics is still the best starting point. But even if you hope to create something wildly divergent from Aristotle’s structures, he makes a persuasive case that there are rules, principles and techniques (call them what you will) to consider before you set about your work as a storyteller, no matter what your chosen field or conceptual approach. “The chief duty of artists is to provide imitations technically as perfect as they can make them,” writes McLeish, “and in Poetics Aristotle offers hints and suggestions for how this should be done.”

William Archer (1856 – 1924) was a Scottish critic, playwright and theorist. A friend of Irish writer

George Bernard Shaw, he was one of the first translators of Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen into English. Here for more about Archer, who explains at the start of Play-Making: “Having admitted that there are no rules for dramatic composition, and that the quest of such rules is apt to result either in pedantry or quackery, why should I myself set forth upon so fruitless and foolhardy an enterprise? It is precisely because I am alive to its dangers that I have some hope of avoiding them. Rules there are none; but it does not follow that some of the thousands who are fascinated by the art of the playwright may not profit by having their attention called, in a plain and practical way, to some of its problems and possibilities.” It’s in Play-Making where Archer cites French drama critic Francisque Sarcey’s definition of drama (one which Mackendrick said was the most useful he ever encountered): “expectation mingled with uncertainty.”

Lajos Egri (c.1888 – 1967) was a Hungarian-born theorist who taught creative writing for many years in New York and Los Angeles (his letterhead reads: “The Egri Method of Dramatic Writing”) and also wrote a number of full-length plays himself (he was also a prolific poet and short story writer). Egri’s book The Art of Dramatic Writing (originally released as How to Write a Play), translated into several languages and described by the Washington Post as a “masterpiece,” has been in print ever since it was first published. In related publicity material, we find this: “Starting his life as a playwright at the age of 10 in Eger, Hungary, Egri migrated to America with his wife, Ilona, whom he married at age 17! In America Egri became a journalist; wrote and produced plays. In his meeting with writers, both the young and immature, and those who had ‘arrived’ professionally, Egri was struck by the fact that the effective ‘bones’ of dramatic writing continued a mystery for many of them. Those who were not succeeding didn’t understand why. Those who were succeeding didn’t understand why, thus, often, could not repeat their performance!” In a letter written to Egri a few weeks before his death, Ray Bradbury wrote, “There isn’t a week that passes that your name doesn’t cross my lips, when people ask me which books to read to help them in their writing career.”

John Howard Lawson (1894 – 1977) was an American playwright, screenwriter and theorist. Avowedly left-wing (he was head of the Hollywood chapter of the Communist Party USA and testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1947), Lawson was an early president of the Writers Guild of America (an interview on the subject here) and years later was one of the blacklisted Hollywood Ten. Author of numerous Broadway plays and Hollywood screenplays, his publications include Film in the Battle of Ideas (1953) and Film: The Creative Process (1964). More on Lawson’s life and work here and here. Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting (in which Lawson cites Aristotle and Archer) is especially useful for students of dramatic construction, describing what Lawson calls “The Cycle of Conflict” and the differences between “activity” and “action” (or, to put another way, between a “situation” and a “story”).

All four texts were published many years ago and so might be considered somewhat antiquated, especially because they employ examples of plays and films (and authors and filmmakers) that contemporary readers may be unfamiliar with. But they are nonetheless expertly written pieces of prose, full of perennial, reverberative ideas that can be endlessly mined for useful guidance when it comes to narrative screenwriting.

Before jumping into all this reading, take a look at this two-hour extract – specifically about story – from the audio/visual project Mackendrick on Film, which was produced to accompany On Film-Making.

For a complete set of clips, go here.

Mackendrick knew that however much he implored them to do so, most of his students would never read texts by Aristotle, Archer, Egri or Lawson, or indeed most anything else on the subject of dramatic construction, which is why he prepared summaries of the first two. These documents can be found in the red box below, alongside other material and downloads created for this website.

A version of Mackendrick’s Aristotle handout, which contains many useful extracts from Poetics, is here. Two translations of the complete Poetics are available online. Here and here for Butcher. Here for Bywater. Here is a modern translation by Hammond. Kenneth McLeish’s translation and short book about Aristotle are both well worth reading.

Mackendrick’s handout on William Archer, which contains a handful of valuable extracts from Play-Making, is here (a shorter version appears in his book On Film-Making). Archer is particularly good on explaining the key notion of point of attack (see here). His book can be found in its entirety here and here.

Extracts from Egri’s The Art of Dramatic Writing – which is a bit long-winded, and many pages of which are taken up with details of specific examples of existing works of drama that you might not know about or be terribly interested in, and has lengthy sections written in a Q&A format, if you like that kind of thing – are here.

Extracts from John Howard Lawson’s Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting are here and here. The text of the entire book is here. Lawson’s other books Film: The Creative Process and Film in the Battle of Ideas are available here and here. Theory and Technique of Playwriting, Lawson’s 1960 book, is here. All texts by John Howard Lawson appear here courtesy of Jeffrey Lawson and Susan Amanda Lawson.

Here for an extract from Mackendrick’s On Film-Making relating to dramatic construction. Here for a glossary of dramatic jargon, as drawn from Mackendrick’s writings. Here for a selection of step outlines, some written by Mackendrick. Here for Mackendrick’s Slogans for the Screenwriter’s Wall, which serve as something of a summary everything contained on this page and more.

If you would rather engage with the basics of dramatic construction from a more contemporary perspective, one can do no better than study the work of David Mamet, the prolific American playwright/screenwriter/director, whose many books and essays (including the penetrating

On Directing Film and Three Uses of the Knife) are useful indeed. Here for a selection of Mamet’s thoughts on the subject (and also his pertinent ideas about filmmaking, not least his articulate description of Eisenstein’s theory of montage). Here for Mamet’s Paris Review interview from 1997, which contains insight upon insight. Another good interview here.

Include into the mix the work of perhaps the best-known screenwriting teacher working today: Robert McKee. No great writer himself, McKee knows enough to borrow from the best, and his book Story is full of good ideas taken from Aristotle and Lawson (both are cited in the bibliography). (N.B.: stay away from his second book Dialogue.) Here for some McKee-isms. Here for an article that contains useful background information about McKee. Here, because such a thing exists, is a critique of his way of doing things.

Someone cited by McKee in his book is Kenneth Thorpe Rowe, a professor at the University of Michigan (where he taught Arthur Miller, who once said of Rowe, “He was a great audience. He loved whatever was good and what was bad he minimized” – which seems like an excellent starting point), whose A Theater in Your Head contains useful ideas. Here for a handful of pages from that book.

This (adapted from a 2014 book) is solid stuff by John Yorke, who can be seen here giving a lecture here. Yorke isn’t wildly inspiring, but his ideas can be useful for beginners. He formulated “Ten Questions,” designed to get any screenwriter out of trouble (though none of it will count for much unless you already have a story in hand): (1) Whose story is it? (2) What’s their flaw? (3) What is the inciting incident? (4) What do they want? (5) What obstacles are in their way? (6) What’s at stake? (7) Why should we care? (8) What do they learn? (9) How and why? (10) How does it end?

Those with more of a theoretical inclination who are seeking to learn more about story structure and filmmaking should take a look at the work of David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, specifically their books Narration in the Fiction Film (1985), Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique (1999), Storytelling in Film and Television (2003) and The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies (2006). At times somewhat arcane, the Bordwell/Thompson texts are nonetheless worth close study, for much practical information can be extracted from them. Bordwell and Thompson also maintain a voluminous website. Dig into pages like this one, or here, then move methodically through the links, and it will likely be some time before you reappear from cyberspace.

There is, inevitably, a continuity of thought running through these texts and, indeed, all competent articulations of the most fundamental principles of dramatic construction, and it’s worth noting that to a great extent, Aristotle, Archer, Egri, Lawson, Mackendrick, Mamet, McKee, Rowe, Yorke and Bordwell/Thompson all say the same things. One might even go so far as to paraphrase Alfred North Whitehead: all writings about dramatic construction are a series of footnotes to Aristotle. You could select any three of these names, ignore the others, and probably not miss anything radically important. In his 1948 book The Human Nature of Playwriting, Samson Raphaelson recommends that students “go to the library and find a book or two on dramatic technique. I don’t think it matters too much which book. Each book has its friends and its enemies among teachers, and I propose that you explore for yourselves.” It’s a good way of thinking about this subject, because there are texts about dramatic construction that I either don’t know about or don’t particularly appreciate, but that work for you, and however imperfectly I might think those books represent the key principles, it’s probable that they do cover the basics and will serve as a good starting point for you. There’s no point in me pushing John Howard Lawson on you if it’s nothing but meaningless jumble. Pick up a different book instead. Or take a completely different approach, and by do doing, learn it all your own way. Frances Taylor Patterson, author of an early study of screenwriting practice – Cinema Craftsmanship (1921) – put it nicely in her 1928 book Scenario and Screen: “An actor tells the story that a friend of his, knowing that he was ambitious to write a play, sent him a copy of William Archer’s Playmaking. When he began to delve into the principles of stagecraft laid down by Archer, he realized that he had learned most of the theories from knocking around the theater over a period of years, playing all sorts of parts and learning all sorts of things by bitter experience. He and Mr. Archer arrived at the same conclusions, but by different routes.” Of course, much of what you might come to absorb from books and practical experience is likely to be wholly commonsensical, things you knew instinctively, without even thinking about them.

Consider also that in 2012 a list of twenty-two “story basic” (detailed commentary here) were compiled by a former employee of Pixar Studios, many of which bear a striking resemblance to Mackendrick’s teachings. Note that several key creatives at Pixar (John Lasseter, Brad Bird, Andrew Stanton – see his TED talk here, in which he mentions William Archer and “expectation mingled with uncertainty” – Pete Docter, Mark Andrews, et. al.) were students in the film school of the California Institute of the Arts when Mackendrick was there (he ran the place between 1969 and 1978, and continued teaching until his death in 1993). It’s unclear whether any of these individuals actually took any classes with Mackendrick, but it seems entirely likely that at one time or another they were exposed to his ideas via some of his many handouts written for and distributed to students. (While we’re talking about Pixar, this, from Michael Arndt, writer of Toy Story 3, is worth a read.) One student most definitely influenced by Mackendrick is Mark Kirkland, who has directed more episodes of The Simpsons than anyone else. “My understanding of character, plot, theme, staging and film grammar all come from Mackendrick,” he says. “I use his ideas every day at work.”

All that said, the ideas on this page are mere guideposts, presented to help you see the bigger picture, to provide you with a toolbox into which you can reach when you run into trouble while writing, to assist you in identifying, diagnosing and, ultimately, remedying problems with your work. To repeat: with your work. As in “work that has already been done.” No one can start writing with a list of the tenets of dramatic construction taped to the wall in front of them, ticking off various things (inciting incident/point of attack, character-in-action, theme, suspense/tension, exposition, foil characters, backstory, dramatic irony, peripety, fuses/foreshadowing, reincorporation, obligatory scene, resolution/dénouement, etc.) as they go. Write something first, then fix it. Here is John Swartzwelder, coincidentally also best known for his work on The Simpsons, discussing his way of doing things, about what some people refer to as a “vomit draft.”

I do have a trick that makes things easier for me. Since writing is very hard and rewriting is

comparatively easy and rather fun, I always write my scripts all the way through as fast as

I can, the first day, if possible, putting in crap jokes and pattern dialogue – “Homer, I don’t

want you to do that.” “Then I won’t do it.” Then the next day, when I get up, the script’s been

written. It’s lousy, but it’s a script. The hard part is done. It’s like a crappy little elf has snuck

into my office and badly done all my work for me, and then left with a tip of his crappy hat.

All I have to do from that point on is fix it. So I’ve taken a very hard job, writing, and turned

it into an easy one, rewriting, overnight. I advise all writers to do their scripts and other

writing this way. And be sure to send me a small royalty every time you do it.

John McPhee (whose Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process is surely one of the best books of its kind) has similar ideas.

Sometimes in a nervous frenzy I just fling words as if I were flinging mud at a wall. Blurt out,

heave out, babble out something – anything – as a first draft. With that, you have achieved a

sort of nucleus. Then, as you work it over and alter it, you begin to shape sentences that score

higher with the ear and eye. Edit it again – top to bottom. The chances are that about now

you’ll be seeing something that you are sort of eager for others to see. And all that takes time.

What I have left out is the interstitial time. You finish that first awful blurting, and then you

put the thing aside. You get in your car and drive home. On the way, your mind is still knitting

at the words. You think of a better way to say something, a good phrase to correct a certain

problem. Without the drafted version – if it did not exist – you obviously would not be thinking

of things that would improve it. In short, you may be actually writing only two or three hours

a day, but your mind, in one way or another, is working on it twenty-four hours a day – yes,

while you sleep – but only if some sort of draft or earlier version already exists. Until it exists,

writing has not really begun.

As Mackendrick explained, his teachings and student handouts “mean nothing when they are first explained. They mean something when they can be related to an immediate and specific problem in what the student is currently working on.” So what you have here on this page isn’t the be-all and end-all of anything when it comes to the theory behind cinematic storytelling, nor even the classical narrative tradition (which has always only ever been just one way of doing things). It’s merely a collection of ideas worth thinking about, absorbing and understanding, then probably moving beyond. The fact is that after reading everything above, doubtless you will be able to think of a multitude of excellent films that appear to correspond in absolutely no way to some of the most basic concepts of dramatic construction, and yet keep audiences thoroughly entertained. As it should be. After all, the trick as a storyteller is to absorb the principles and, by doing so, find your own unique techniques, your own way of doing things. The learning curve kicks in when you start exploring how each film you watch works within the “rules,” how some subvert them creatively, how some apply them with either rigidity or subtlety, how some fail at every turn.

In The Art of Photoplay Making, published in 1918, Columbia University screenwriting instructor Victor Oscar Freeburg explains that the writer must construct their story “as deliberately as if he were the architect of a house. An architect has to recognize and obey certain unchanging laws of gravitation, equilibrium, tension, and stress. He has no choice in the matter. He cannot alter, ignore, or repeal these laws. In the same way the author must recognize and obey the laws of the human mind, laws which have not changed since the world began. People become interested, pay attention, get excited and calm down, remember and forget in exactly the same way today as when the first savage told a story or scratched the rude picture of a beast on the wall of a cave.” It’s understandable why so many people appear to be resistant to things like “rules” when it comes to creative writing, but I nonetheless find it hard to disagree with Mr. Freeburg on this point.

A useful take on this (useful because it doesn’t come from a practitioner or theorist of cinema) can be found in the work of cartoonist Scott McCloud, in his wonderful book Making Comics, which presents its important ideas entirely in comic form, and on one of the first pages of which we read: “I won’t tell you the ‘right’ way to write or draw because there’s NO SUCH THING. Any style, any approach, any tool, can work in comics if it’s right for YOU. But, your choices NARROW when you want your comics to provide a specific REACTION in readers. That’s when certain methods might do the job for you – and others WON’T. There are NO LIMITS to what you can full that BLANK PAGE with – once you understand the PRINCIPLES that all comics storytelling is BUILT upon. In short: THERE ARE NO RULES. And HERE THEY ARE.” (Several of McCloud’s key ideas precisely mirror Mackendrick’s. Of the audience: “We want them to UNDERSTAND what we have to tell them…” is a version of Mackendrick’s constant emphasis on clarity of storytelling. McCloud’s “…and we want them to CARE enough to stick around ’til we’re DONE” is, of course, a version of the question the narrative filmmaker is hoping that the audience is constantly – if unconsciously – asking itself: “What Happens Next?” Of the basic facts of each and every scene, of the information flow offered to the reader, McCloud writes of “Who does what, where it’s done, how it’s done and so forth,” which is similar to Mackendrick’s limerick ending with “who should do what with which and to whom.”)

As is by now hopefully clear, taken together the ideas presented here on this webpage can be nothing but a starting point for students of dramatic construction. For no one should they become the final word. As Mackendrick writes at the start of On Film-Making, the handouts he created for students represent only “my own method of filmmaking, the one that suits me. If I bully you into trying things my way, it is not because mine is the only way, or even the best way. Certainly it will probably, in the end, not be your way. But I suggest you make a real effort to follow my formulas as a temporary exercise. Not to ‘express yourself.’ Not yet. You can do that as much as you like, later. So put aside your hunger for instant gratification and creativity, at least for long enough to understand some basic ideas and practical pieces of advice that you are perfectly entitled to discard later.”

“Dramatic Construction” was the name of one of two classes Mackendrick taught for several years at CalArts (and also of one of the two sections of On Film-Making). The other was “Film Grammar,” the basic tenets of which can be gleaned from two of the most important books ever published on the art and craft of filmmaking: Film Technique by Vsevolod Pudovkin (extract here) and Film as Art by Rudolf Arnheim, both of which were strong influences on Mackendrick and his conceptual understanding of cinema when it came to his thinking as a teacher. The books are available here and here. Why is a consideration of film grammar so important to the student of dramatic construction? Because form can never be entirely separated from content. Writing for the cinema requires an understanding of how it functions as a storytelling medium at the most fundamental level, which is through images, not words. Here for Mackendrick and others discussing film grammar.

Creating a character relationship map for your story – and by so doing making clear the interconnections between your fictional creations – may help you understand what tensions potentially exist between them (i.e. what is driving the story forward) and in which direction the narrative might usefully move.

The condensed version of all this comes from John le Carré, who offers up a good starting point when it comes to determining what is a SITUATION and what is a STORY: “‘The cat sat on the mat’ is not a story. ‘The cat sat on the dog’s mat’ is a story.” If you’re still lost after that, fairy tales are a good place to start.

“Write from experience” is the worst piece of advice ever offered in a screenwriting class. Use your imagination, for God’s sake. On that note, probably better to stay out of school altogether. (Mamet: “Education is the worst thing to happen since kale.”) If you are, for whatever reason, shackled to education, remember to think for yourself. Nobody knows anything. Kenneth McLeish: “Aristotle’s conclusions were never meant to be prescriptive; they were, rather, a summary of all evidence so far available, with conclusions drawn from it. In his view, new material and new evidence were constantly appearing, and theories should be modified to take account of them. His surviving works – about one-quarter of the total attributed to him – are not finished treatises so much as interim reports, often in the form of notes and containing accumulations and accretions of material made over many years.” The same could be said for all the writing cited above.

One more gem from Ms. Patterson, on the pitfalls of screenwriting, also from her book Scenario and Screen, a chapter entitled “The Scenario Editor,” in which she notes that such people “have to harden their hearts to the pathos of futile effort and the appalling waste of human endeavor which day after day their mail reveals. A constant tide of manuscripts, penned by all sorts and conditions of people, must be stemmed by rejection slips and turned back to its source… Most of the people who besiege scenario offices have an unshakable belief that they can write, a presumption which is rarely substantiated by any particular performance. Usually the more the would-be writer talks of his ability, the less evidence of it can he produce. The urge to write photoplays seems to be entirely independent of either talent or equipment. People lacking both present themselves at the offices of the scenario editor with a chronicle of banalities culled from a too accurate observation of all the cheap situations that have been in the producer’s bag of tricks for the last ten years. Rarely do they exhibit a gleam of originality. Indeed, their minds are no so much occupied with the fashioning of a good story as with their fair rewards.” Nearly a century later, plus ça change…

Mackendrick wrote of Pablo Picasso that he “demonstrated a complete command of figurative painting before he went on to reinvent the language of visual art.” Apparently Picasso explained that “Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.” We have something to learn from anyone who created these two images.

Mackendrick wrote of Pablo Picasso that he “demonstrated a complete command of figurative painting before he went on to reinvent the language of visual art.” Apparently Picasso explained that “Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.” We have something to learn from anyone who created these two images.

Don’t for a moment worry about whether your script is correctly formatted (i.e. based on what you believe are industry standards). Write Leslie Peacocke in his book Hints on Photoplay Writing, published in 1916: “Don’t make the mistake of thinking the market success of your submitted scenario rests upon technical instructions about how to build the scenes in front of the camera. Studio department heads are paid to take care of that. What they want from you is an idea.” Nothing has changed in a hundred years. Know that at this stage of the game, writing a shooting script is not your job. Creating a story is all that matters. And note too this advice from Capt. Peacocke: “Do not attempt to be ‘literary.’ Stick to simple language – the simpler, the better – as the reader is anxious to get at the heart of the story and cares nothing about literary style.”

Finally, here are some ideas that might be worth trying out. Perhaps script them (this probably includes a shot breakdown, and perhaps only a smattering of dialogue), then film them. From whose point of view should these little tales be told? What is the point of attack (i.e. what it the most effective way of starting the story)? Perhaps these vignettes are self-contained, or perhaps they lead more, bigger storytelling. Obviously it’s up to you. There is no right or wrong. The only thing to remember is Mackendrick’s thoughts about “process not product.” Think about how much you would learn should you attempt something like this. (Remember that talk above about the learning curve.)

Here is Vladimir Nabokov, from an essay about Charles Dickens.

I have a sneaking fondness for the story about Dickens in his difficult London youth one day

walking behind a workingman who was carrying a big-headed child across his shoulder.

As the man walked on, without turning, with Dickens behind him, the child across the man’s

shoulders looked at Dickens, and Dickens, who was eating cherries out of a paper bag as he

walked, silently popped one cherry after another into he silent child’s mouth without anybody

being the wiser.

This is from John Muir. It could presumably all be done on foot, without a horse. Bicycles maybe?

I had climbed but a short distance when I was overtaken by a young man on horseback,

who soon showed that he intended to rob me if he should find the job worth while. After he

had inquired where I came from, and where I was going, he offered to carry my bag. I told

him that it was so light that I did not feel it at all a burden; but he insisted and coaxed until

I allowed him to carry it. As soon as he had gained possession I noticed that he gradually

increased his speed, evidently trying to get far enough ahead of me to examine the contents

without being observed. But I was too good a walker and runner for him to get far. At a turn

of the road, after trotting his horse for about half an hour, and when he thought he was out

of sight, I caught him rummaging my poor bag. Finding there only a comb, brush, towel, soap,

a change of underclothing, a copy of Burns’s poems, Milton’s Paradise Lost, and a small New

Testament, he waited for me, handed back my bag, and returned down the hill, saying that

he had forgotten something.

This is more or less something I saw myself while walking downtown, on Waverly Place, just off Broadway, many years ago. Let’s call it The Beggar’s Cup – a simple drama, with a three-act structure. Equilibrium, the unbalancing of equilibrium, the (apparent) restoration of equilibrium. The bare bones. Elaborate as necessary.

Walker moves down the street.

Beggar standing, cup in hand.

Walker accidentally knocks the cup from Beggar’s hand.

Walker apologises and picks up Beggar’s cup.

Walker pulls out some change and puts it into the cup.

Walker moves off down the street.

Mackendrick was much taken with this vignette, as written by Cesare Zavattini, from his book Sequences from a Cinematic Life. How would you film this?

LOVE – I took shelter in a doorway, from the house opposite came the notes of a waltz, the rain stopped and on the balcony of that house a young girl appeared dressed in yellow. I couldn’t see her clearly up there, I couldn’t have said “her pink nostrils,” but I fell in love, perhaps it was the odor of the dust raised by the downpour, perhaps the glistening of the drainpipes as the sun reappeared (we are followed on tiptoe by someone who makes the clouds, causes noises in the streets only so that they will drive us where it suits him, but in such a way that we blame the clouds and the noises). The girl on the balcony dropped a handkerchief, I ran to pick it up, then rushed through the door, up the steps. “What’s your name?” I asked, out of breath. “Anna,” she answered, and vanished. I wrote her a letter of a kind I’ve never written again in my life; a year later we were married. We are happy; Maria, Anna’s sister, visits us often, they love each other and are very similar; even their faces are alike. One day, we talked about that summer afternoon, about how Anna and I had met. “I was on the balcony,” Maria said, “and all of a sudden I dropped my handkerchief. Anna was playing the piano. I said to her: ‘I dropped my handkerchief, a man is bringing it up.’ She was less shy than I was, she went to the door and met you. I remember as if it were yesterday, we were both wearing yellow dresses.”

John Sorensen, who studied at CalArts with Mackendrick, recalls something told to him by his teacher that doesn’t appear in any handouts or interviews, a tale from long ago. Mackendrick and his wife had a cat, who had kittens, but homes couldn’t be found for them all, so one evening Mackendrick reluctantly gave the animals to a boy who agreed to take them to the river to be drowned. When telling the story to students, Mackendrick gave special attention to the haunting image in his mind of the bicycle’s lamp getting smaller and smaller as the boy rode away with a bag full of kittens. I think this scenario would make an interesting short film. Try it with only ten words of dialogue.

This line intrigues me. It’s from an article that references the David Rabe play The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel, which the author notes “begins with a scene that’s completely indecipherable until it’s re-played at the very end.” An idea that might serve as the starting point for a writing exercise.

Andrew Sarris wrote this many years ago. Perhaps the basis of an exercise in dramatic construction and film grammar?

The choice between a close-up and a long-shot… may quite often transcend the plot. If the story of Little Red Riding Hood is told with the Wolf in close-up and Little Red Riding Hood in long-shot, the director is concerned primarily with the emotional problems of a wolf with a compulsion to eat little girls. If Little Red Riding Hood is in close-up and the Wolf in long-shot, the emphasis is shifted to the emotional problems of vestigial virginity in a wicked world. Thus, two different stories are being told with the same basic anecdotal material. What is at stake in the two versions of Little Red Riding Hood are two contrasting directorial attitudes toward life. One director identifies more with the Wolf – the male, the compulsive, the corrupted, even evil itself. The second director identifies with the little girl – the innocence, the illusion, the ideal and hope of the race.

I have always wondered if the Preston Sturges film Christmas in July could be used as the starting point for an exercise in dramatic construction. Given that the film is only 67 minutes long and contains no subplots, how might it be expanded into 90 minutes? This isn’t to say the film isn’t good (it’s very good), only that it would be an interesting experiment to see in which inventive ways the story might be fleshed out into a more traditional length for a feature film. New characters? Storylines? Etc. Consider another Sturges film, The Lady Eve, and build a simple exercise around it. Precisely halfway through the film, Charles Pike discovers the truth about Jean Harrington. Your job is to re-write the second half of the film. A completely different ending might be the result, or you might devise a new series of events that nonetheless bring the characters to the same end point as Sturges himself does.

This happened to a friend of mine, many years ago. Film this however you want (as an experiment, perhaps use only one close-up). Deliver up as much backstory as you see fit. Include as much dialogue as you think it needs. Consider whether the boy’s feelings about the crossing guard are purely a product of his imagination.

An insecure young boy is newly arrived in town with his family. He is intimidated by what he feels is the cold stare of the crossing guard outside his school. Each morning he walks towards school, each day she stares him down. One morning, he spots a ten dollar bill on the ground, which he instantly imagines spending on sweets, his method of choice to quell anxiety. But he is so aware of this woman that he is unable to muster the courage to satisfy his urge and bend down to pick up the money. He walks on as though nothing were there, staring at the crossing guard as he walks past her.

To wrap things off, this is from Flannery O’Connor:

I wrote a story about a tramp who marries an old woman’s idiot daughter in order to acquire

the old woman’s automobile. After the marriage, he takes the daughter off on a wedding trip

in the automobile and abandons her in an eating place and drives on by himself.

Finally (again), the question must be asked: does any of this – all this talk of dramatic construction – actually count for anything? Do the books and chapters and articles out there on the subject, all the instructors lecturing, all the screenwriting classes going on around the world as you read this – does it all make for better writing, better screenplays, better storytelling? Who can say? Certainly there are those who believe that this approach to story and screenwriting, and its teaching, is the most pestiferous there is. The ubiquity of how-to books, as Steven Price writes, means that screenplay has, for better or worse, been solidified “into an object with more precisely definable characteristics than at any time since the end of the silent era.” This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, though try telling Adrian Martin that. He wrote an especially eviscerating, if not entirely convincing, critique (it gives the corpus too much credit: “The script manual industry is poisonous because it has helped cheapen and limit what is possible in cinema”). All I can say for sure is that I generally enjoy reading such things because every one, however compelling or unimpressive, makes me understand how good is Mackendrick’s writing.

And so, the industry that purports to teach the secrets, thrives.

And so, never forget that anyone can write a first act.

And so, as you embrace the terror of the blank page, read this classic about storytelling, then go here – both antidotes to all this mishegas.